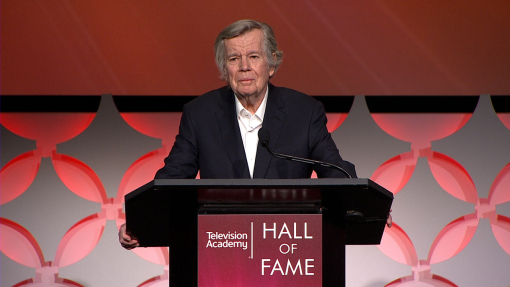

Try to imagine the last two decades of television comedy without Taxi, Cheers, Frasier, Friends, and Will & Grace. Now try to imagine any of those shows without the imprint of director and producer James Burrows. Beer without the suds? Champagne without the bubbles?

In a remarkable career, Burrows has brought significance to the role of the sitcom director in a way that rarely occurs, and cultivated a mainstream appetite for a certain brand of urban, upscale living-room comedy. Along the way he has become the most honored television director in history, nominated for 21 Directors Guild of America awards, not to mention nominations for Emmy awards nearly every year for the past 25 years (he’s won four DGA awards and 10 Emmys).

Much of his success comes from talent and tenacity — Burrows works hard at his gift for funny and his bent for relevance, making sure that the envelope is pushed and the laughs are rat-a-tat-tat. “My mind is never a blank. If something isn’t funny, I just won’t quit. I’ll try nine ways to make it funny. I’ll change the line, or find a funny position for the actors,” he relates.

Part of it has to do with consistency — in a medium where directors are itinerant, he has bucked tradition, becoming famous for shaping shows from start to finish, directing hundreds of episodes of Cheers, for example, and every episode in the smash-hit eight-year run of Will & Grace. Part of it is his reverence for the use of a live audience, carrying forward the Broadway theater traditions he learned while growing up, and the mentorship he absorbed as an apprentice at MTM Productions.

Yet it was his upbringing in theater that nearly turned him away from a career in show business. He sought to avoid competing with the long shadow of his father, playwright and director Abe Burrows, a Broadway icon whose hits included Guys and Dolls and How to Succeed In Business Without Really Trying.

“I don’t have any real plans for the future. However, math and science interest me most,” he wrote in his entry application to Oberlin College, from which he graduated in 1962. But from there, he went on to earn a master’s degree in drama at Yale, followed by a five-year period where he worked somewhat reluctantly as an assistant stage manager, often on his father’s shows. During that time, he made a fortuitous connection — the star of the ill-fated Broadway production Holly Golightly, Mary Tyler Moore.

Some years later, while staging regional theater, Burrows caught Moore’s smart new television sitcom, and a vision of his future clicked. “They were doing 30-minute plays once a week in front of a live audience. I was doing 120-minute plays, and I thought to myself, ‘I could do that.’”

Even better, he could do it in Los Angeles, far from the Manhattan theater world, in a medium in which he could make his own name.

He wrote a letter to Moore, and his theatrical background sparked interest from her husband, Grant Tinker, who invited him to apprentice at MTM beginning in 1973.

Burrows began as a paid observer, initially of The Bob Newhart Show on Stage 17 in Studio City (the very stage where Will & Grace would be shot decades later), and then of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, on which he bonded with director Jay Sandrich. “He has been my mentor for so many years,” says Burrows. “For me, he is the true genius of this medium.”

Burrows’ first assignment was an episode of Moore’s series, an experience he still remembers as “thrilling, exhilarating,” not least because the script was sub-par and he had to fight so hard to help the cast make it work. “I invoked Chekhov, Strindberg, Kaufman and Hart — anything that would help get them through it,” he recalls.

The producers were duly impressed. Burrows went on to direct episodes of Rhoda, Phyllis, Laverne & Shirley and other comedies before becoming the principal director of Taxi in 1978.

That series proved to be his first opportunity to really shape a cast and a show, and it was a challenge. “You had incredibly divergent styles,” he says of the ensemble cast that included Judd Hirsch, Danny DeVito and Andy Kaufman. “It was everything I could do to make that show go.”

But go it did, creating a hard-sought cohesion between the cast, not to mention making room for the unorthodox brilliance of Kaufman’s alter-ego Tony Clifton (“It was a marvelous day to be on the Taxi stage when Tony Clifton arrived,” Burrows recalls) and the prolonged laughter of the hilarious “Slow down!” routine provoked by the question from Reverend Jim (Christopher Lloyd), “What does a yellow light mean?”

Then came Cheers. Burrows collaborated with writers Glen and Les Charles to create a classic comedy about a group of ne’er-do-well Boston barflies and a waitress, Diane, who made a point of displaying her education to the irritation of all.

Burrows recalls, “We spent two months talking about these characters, and then the boys went off and wrote a script. I remember reading it and saying, ‘The Charles Brothers have brought radio back to television!’ It was so literate, so smart and upscale. There were jokes about Schopenhauer and Updike and Freud and Jung, and we didn’t care if the audience knew who these people were.”

That made the going somewhat dicey at first. Cheers struggled in the ratings for the first two seasons. NBC would have canceled it but for the intervention of network president Brandon Tartikoff. The show went on to become a comedy classic, winning 28 Emmy Awards during 11 seasons. Burrows directed 244 of its 275 episodes. “That show was my baby,” he says. “I was there at the beginning, to help shape the cast, and I was there at the end.”

The series was life-changing for a number of reasons. After that, he says, “I could get my pick of any show I wanted to do.”

The industry came after him to direct innumerable pilots, paying a premium to get his imprint on a series at the outset. Among them was the Cheers spinoff, Frasier, which Burrows helped launch in 1993 and stayed on board with through 32 episodes, and Friends, on which Burrows directed the pilot and 15 more episodes in the first two years.

In 1998, Burrows and his collaborators somehow snuck a classic odd couple love story about a single urban gal and her handsome gay flatmate into the living rooms and hearts of mainstream America. “Will & Grace was the most pushing-the-envelope show I’ve ever done, and hopefully it’s made America a little less afraid of gay people, after having them in their living rooms every Thursday night for so many years,” Burrows says.

He executive produced and directed every episode, generating hilarity so consistent that viewers’ addiction to the show seemed to override any concerns about its bawdy and outrageous content. “We went to the stratosphere with a lot of the jokes,” says Burrows, “but the characters had an innocence that somehow took the curse off the material.”

As a director, Burrows says his main job is to “radiate confidence and get the actors to walk that comic plank to places unknown. With my track record, I bring a lot of power to the set, and I try to pass that along to the actors. Of course, after a while, they own the roles, and you don’t have to work as hard. At that point, my style has to do with making sure they’re having a good time, because their fun will transmit to the screen.”

His method includes running every scene twice before the live studio audience, and having writers furiously re-write between takes if the material doesn’t fly. He tends to listen to his shows, rather than watch the monitor, believing that comedy abhors silence. “I’m from theater,” he explains. “If you don’t keep it moving, you lose the audience.”

And while he has never written — “I don’t have writer’s logic” — his contribution is innate. “I seem to be able to bring a sense of humanity and camaraderie to the core cast. People feel comfortable watching these people, in a way that transcends the television screen.”

One thing is certain: in a medium where directors tend to be low on the totem pole, Burrows has worked to bring respect and a higher profile to the industry’s view of the craft.

Currently directing and executive producing the CBS comedy The Class, Burrows says his desire to keep the laughs coming is something that he treasures. “I don’t have to work anymore. I do it because I have so much fun doing it.”

If he ever does walk away, he can point with pride to an era when, via the magic of syndication and cable, his shows are virtually everywhere. “I think at some point within a day, you can always find one of my episodes playing somewhere,” he surmises. “And that’s kind of cool.”

This tribute originally appeared in the Television Academy Hall of Fame program celebrating James Burrow's induction in 2006.