For W. Kamau Bell, his Showtime docuseries, We Need to Talk About Cosby, may be the culmination of everything he's done as a comic, activist and storyteller.

He grew up on Bill Cosby's TV series, from the kid shows The Electric Company and Picture Pages to NBC's hit sitcom The Cosby Show. He's a stand-up comic who was once inspired by Cosby's talent as a storyteller and performer. He's a Black man and advocate for equality who is well aware of how Cosby was once viewed as an exemplar of Black excellence and advocacy.

But beyond that, Bell has honed his chops as a TV host — first, on FX and FXX's late, lamented late-night show Totally Biased with W. Kamau Bell and later as the host–executive producer of CNN's United Shades of America (for the latter, he was Emmy-nominated seven times, winning on three occasions for outstanding unstructured reality program). He directed a documentary in 2018 for A&E's Cultureshock series on Chris Rock's breakthrough HBO stand-up special, Bring the Pain. And he's grown adept at holding difficult conversations on tough subjects, aiming to advance social progress.

So what possessed Bell to make a four-episode docuseries that tries to balance William H. Cosby's achievements against the terrible allegations of rape, drugging and sexual assault against him?

"I was a Black kid born in the '70s, so Cosby always took up a lot of space in my life and then in my heart," Bell says. "I was always sort of walking in these giant Bill Cosby footsteps going, 'I'm not going to be him, but I got it. That's the kind of career I want to have.' I wanted to do good in the world the way he does good in the world. And then all the allegations come out. And like a lot of people in our generation and older, I was wresting with, 'What does this mean? How do you process all this?'"

His process involved assembling a docuseries that features forty-two people talking about Cosby's legacy in the wake of allegations by more than sixty women that he drugged and sexually assaulted them, starting in the 1960s.

Bell's sources include commentators and academics like Jelani Cobb, Jemele Hill and Marc Lamont Hill, comedians like Godfrey and Chris Spencer, former Cosby colleagues like Doug E. Doug and Matt Williams and actors like Michael Jai White and Gloria Hendry. Also heard are eleven women who allege they were assaulted by Cosby — and Bell says early in the docuseries that he believes their allegations.

One thing he didn't do was reach out to Cosby himself for comment — even after the former superstar, who was convicted of sexual assault in 2018, saw his conviction overturned by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in June 2021 and subsequently left prison.

"We did have conversations about, 'Should we reach out?'" Bell says. "That would certainly get [attention]... but it felt like, at that point, it would have been turning on the survivors. It would have been totally disingenuous, because we never said, 'Oh, by the way, we're going to reach out to Bill Cosby.' It would have felt like a complete violation of their trust in a story that's about a violation of trust."

Cosby issued a statement through a representative days before the docuseries debuted on Showtime, calling Bell a "PR hack" and denying all allegations made against him. In part, the statement read: "Mr. Cosby has spent more than fifty years standing with the excluded.... Mr. Cosby vehemently denies all allegations waged against him. Let's talk about Bill Cosby. He wants our nation to be what it proclaims itself to be: a democracy."

Bell spoke at length with emmy contributor Eric Deggans about We Need to Talk About Cosby, including early reactions, why he didn't initially plan to narrate it and why he feared the project might be dead when Cosby was released from prison last year. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What has been the reaction to your docuseries so far?

It's been received way better than I hoped it would be. That may say more about me than anything else. But yeah, I have been totally overwhelmed by the positive reviews and was expecting the negative ones. I've never done anything that has been this well received in my career. And also this divisive.

I read a piece in which you said you were afraid of what was going to happen when this was released. What were you afraid of? And did it happen?

I spent a lot of time trying to think of how people could attack it. I very early on realized the people who would probably be the most mad were the ones who were never going to watch it. So whenever I see things come across my social media feed — and I've really pulled back from social media — [often they] are clearly attacks that have nothing to do with the content. I can sort of let that go.

[But] I don't know on balance where my career ends up after this. I would imagine that there might be some circles of people who agree with what the [series] is doing but feel like maybe I'm a little radioactive. I respect the fact people don't think it's just a thing to sit back and watch. They think it's something to be engaged with and then talked about afterwards.

I know you were focused on doing right by the survivors who shared their stories. Do you have a sense of how they've responded to it?

I've heard from many of them. They didn't all watch it right away, because I think everybody comes to this differently. But overwhelmingly, the response from the survivors is that they feel we did something they hadn't seen before with their stories — [we showed] them talking about things that aren't just their time with Bill Cosby.

Those are the responses I was the most concerned about because I would not want them to think they wasted their time. Especially because we filmed during the pandemic, and they could have gotten Covid from coming to a set. I [also] think that's what kept me going when I was making it. I couldn't call Showtime and tell them, "I've pulled a hamstring. I can't finish it."

Or "My subject just got let out of jail...."

Exactly! [Laughs] I kept working on this because [the survivors] gave me so much time and so much of their stories. And the fact is, I've heard from many of them, heard from people's family members who passed on messages that they appreciate how [the series] was put together.

Well, you do cover a lot of ground. I interviewed Stanley Nelson recently, and he was very complimentary of your film. And that's from an Oscar-nominated, Peabody-winning, MacArthur "genius" grant-getting documentarian.

That means a lot. The one thing that I wasn't prepared for is [for] actual filmmakers to like the film. I feel like I graduated. You know, I dropped out of the University of Pennsylvania when I was like nineteen and started taking filmmaking classes at Columbia College in Chicago, which is like a media art school. Back then they were still cutting film with razors and taping things together....

I realized at the time, "I don't want to be cutting things with a razor. This is too hard." So I started to do comedy instead. But there was always this thing inside me that wanted to be a director. And so my life has brought me to a place where I am a director, even though I did it the most non-director-y way possible. I'm in awe of the fact that I ended up in this place right now.

Well, you're not alone. Questlove has made Summer of Soul and Dave Grohl has directed documentaries. Still, does it feel weird, being known mostly as a performer and stepping into this world where the Spike Lees and the Stanley Nelsons and the Ava DuVernays are kind of your peers now?

Well, I'm a stand-up comic and I'm the same age as Dave Chappelle — well, a few months older — so, I'm always aware that you can be doing the same job, but there are some people who are ahead of you. Kevin Hart and I, maybe we both have "comedian" on our tax forms, but we're doing different things.... My income is a rounding error on his taxes. In show business, you can't really compare yourself to these other people, because they're on a different path.

I definitely feel like there are opportunities that I have that only exist because of how the media landscape has shifted and how the access to directing has shifted.

Does this feel like a culmination of all the things that you do?

Yeah, all these disparate elements of my career have come together in this moment. Like, you know, if I'm a Black man born in 1993, rather than 1973, I don't look at this the same. If I wasn't raised by a mom who's like, "You got to do good in the world in addition to being good" "in your job," I'm not looking at this the same.

And suddenly documentary films [change].... People with big personalities are making them, whether it's Michael Moore or Morgan Spurlock. And working on [CNN's United Shades of America], I'm working very closely with directors on every episode. So, yeah, I have been in some sort of boot camp for this, but I didn't know it at the time.

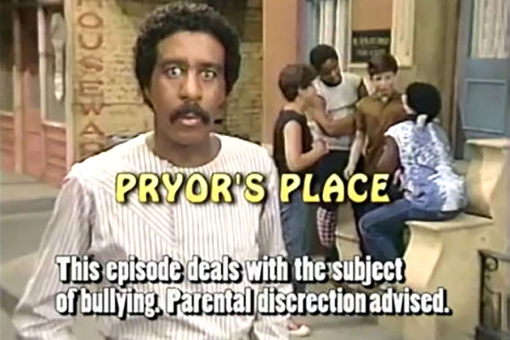

How did you arrive at this idea? You've spoken previously about how it was connected to the way Bill Cosby spurred Hollywood to use Black stunt performers, by insisting they not paint white stuntmen with black paint on his mid-'60s TV series, I Spy.

I read an article about Nonie Robinson's documentary [the as-yet-unreleased Breaking Bones, Breaking Barriers] on Black stunt performers. [Robinson said], "I interviewed [Cosby] for two hours but we're going to cut the footage because of all the accusations." I kept waiting for that documentary to come out. At the time I [thought], if we don't tell that story, we're going to lose the history of these Black stunt performers. These are important stories.

[But] for me, it was watching [ESPN's documentary] O.J.: Made in America by Ezra Edelman, watching Surviving R. Kelly by Dream Hampton. And sitting in an office at Boardwalk Pictures, having a conversation with [executive producers] Andrew Fried and Jordan Wynn about comedy docs and why they're not better and how would you do one about a disgraced comedian?

Canceling performers who have done — or are accused of having done — terrible things is almost the easy way out for fans and consumers. They can eliminate that performer from their lives without grappling with the implications of that hole in history.

Yeah, if you look at Bill Cosby as just a comedian, you can go, "Well, who cares? We'll get another comedian," right? But what we're saying is, it's bigger than him just being a comedian. He actually was a change agent in Hollywood, which is hard to say because of all we know now.

Cosby is seminal to the history of Black people in show business because he, after Dick Gregory, kicks the door open for Black comedians. On late-night television, Bill Cosby walks through that door and manages to build a career that changes show biz forever. And that makes it possible for somebody like me, ironically, to make a documentary like this. And I'm always about conversations that are difficult. How do you hold seemingly conflicting ideas in your head at one time?

How did you end up narrating this?

It was not pitched with me doing narration. But once we realized we weren't going to get some of the most famous people or the people most connected to him, [Showtime said], "The audience needs to know, where is this coming from? We need somebody to lead us through this." At that point, I was really not excited about that idea because I [thought], "Oh, the heat's going to be even hotter under me," you know? [Laughs]

And in your narration, you say pretty quickly that you believe the accusers.

Once I committed to doing it, I was very clear: I have to say early on that I believe the survivors because this is not a true-crime thing. I don't want anybody to think, "Did he do it, or did he not do it?" And especially after having the survivors come and sit down in these interviews, I don't want them to think that I sold them down the river or was trying to play fast and loose with what I told them.

So that line was one of the first things I recorded. But it was a scary thing to say, because a lot of this doc is about how I haven't figured out how to say this stuff out loud. And the Bill Cosby of it all — he was in prison when we started. When he got out, he very quickly was talking about developing his own documentary. He's been very clear about [denying the allegations]. We have plenty of footage of him in it, but he's never wavered off that.

This docuseries puts you in the middle of a fissure in Black America. Plenty of Black folks believe the accusers, but others are suspicious.

This is, again, about holding seemingly competing ideas at the same time. Some of the people who are defending Bill Cosby will highlight the fact that America is a racist place and that America loves to see Black men fall. And there are times you can point to in America's history when white women have accused Black men of doing something they didn't do.

There's also this idea that these women who accused Bill Cosby are all white. That's not true — at least a third of them are Black women. There are certainly elements of white America and the white power structure that are happy for Bill Cosby's downfall because they're always going to be happy for the fall of a Black man, especially a powerful Black man.

But Bill Cosby, as a powerful Black man, has access to the levers of the justice system in a way that if he was just William Cosby from North Philly, he wouldn't have. I think people are trying to split those things and go, "America is racist, so we can't believe these women." And that doesn't hold water. If you know how sexual assault and rape works in this country — how [victims] are generally not believed, that it's still underreported and that we don't have mechanisms for justice and healing when women experience sexual assault and rape — that can also all be true.

Tell me about the moment when you heard Cosby was getting out of jail and you feared you might not finish the project.

I mean, it was more than fearing I wouldn't be able to finish the doc. I feared I was about to fall off planet Earth. I got a text message from a friend who said, "Your doc just got more interesting."

Nobody who was tracking this on our side had any sense that this was coming. It's like the [Food Network] show Chopped. These are the ingredients in the mystery basket, and you just have to make what you can out of it.

What's the next stage of this discussion, beyond what you were able to get to in the series?

Clearly, this is about a systemic failure in show business. Or, as I say, it's not a bug, it's a feature. The feature protects powerful people.

For me it's about, how do we create better mechanisms of safety, specifically in this business? Where it is clear what is over the line and no matter where you are on the call sheet, [if you do something wrong], you have to be stopped. Somebody shouldn't lose their job because they saw you doing something you shouldn't have been doing.

What have you learned here that will help you in other projects?

I have accepted that I'm drawn to these difficult, charged conversations. I'm a huge fan of documentaries, so I want to direct more. But I don't want to always make it something that is divisive in the way this is divisive. There are a lot of charged subjects that people are confused by or don't understand. But yeah, I have learned to accept this is what I'm here to do, and I'll do it until the doing is done.

The executive producers of We Need to Talk About Cosby are W. Kamau Bell (who also directed), Andrew Fried, Katie A. King, Vinnie Malhotra, Dane Lillegard, Sarina Roma and Jordan Wynn. The docuseries is available on Showtime.

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine issue #6, 2022, under the title, "Talking It Out."