They never raised their eyebrows to convey importance or surprise. They didn’t bob their heads, nodding, to emphasize finality. They didn’t shake their heads from side to side to suggest trouble. They didn’t frown and knit their brows together to impart compassion. They didn’t smile at you to show what wonderful people they were or to take the edge off all that nasty, unpleasant information they were giving you. Above all, they didn’t talk to you with the now-I-know-my-ABC’s inflections of a kindergarten teacher. And here’s a real killer:

“We believe,” Jim Lehrer says, “that the people we interview are more important than we are.”

God! And humility, too? How the hell did Lehrer and Robert MacNeil ever make it as TV news anchors?

“I’ll tell you something even more stunning,” Lehrer added. “We believe — now this is going to shock you — that the people who watch our program are as smart and as caring and as nice as we are! Can you believe that?”

Sounds more like an explanation from Mister Rogers — but then, MacNeil and Lehrer’s attitude toward news is so wildly fundamental as to be almost subversive: report information responsibly to the people because it is important and they need to know. Doesn’t leave a lot of room for folksy “tosses” to the wacky weatherman. Cold enough for you, Dr. Larry?

MacNeil and Lehrer are even more of an anomaly than just a couple of deep-rooted journalists in a forest of capped-tooth, malaprop-spitting news readers. They have, in various other lives, been newspaper editors, actors, Marines, disc jockeys, foreign correspondents, aspiring playwrights. They share a journalistic history that includes covering the birth of the Berlin Wall, the death of John F. Kennedy (both were with the President’s motorcade in Dallas that day), the Cuban Missile Crisis (MacNeil was in Cuba, under house arrest, at the time), Watergate, and every major story since. And Lehrer is an authority — practically a museum, judging by his memorabilia-laden Arlington, Virginia, NewsHour office — on the history of the American bus, of all things.

Most remarkably, they’re both writers — real, honest-to-God, successful, published, creative writers — with an array of roman a clefs, mysteries, personal recollections, and novels behind them. Lehrer, who includes among his credits the screenplay for the film Viva Max!, is downright prolific (his 11th novel, Purple Dots, is a Washington thriller). We’re not talking celebrity authors here, either. MacNeil and Lehrer grew up in a world of letters, long before either contemplated careers in journalism, careers that would eventually converge and make them the longest-running news team in television history.

When you think about it, it all sounds almost un-American! Two smart, educated, analytical human beings bringing a smart, educated, analytical news program to a smart, educated, analytical audience. In the relentless televised orgy of soundbites and car chases, how is such a thing possible? Three words: Public Broadcasting System.

“Jim and I,” said MacNeil, “were, and he is now, not subject to the fundamental pressure of the commercial networks, and that is to win, or do your damnedest to win, that time slot. That is a huge psychological difference. It means you don’t have a hundred vice-presidents leaning over your shoulder saying, ‘Change the set, or the way you comb your hair.’”

It also means, above all, emphasizing content. In this image-mad society where writers are now sterilely, if not derisively, referred to as “content providers,” the drones who provide that inconvenient, necessary stuff for packaging and marketing, the success and durability of writer-editors MacNeil and Lehrer in television news is almost confounding.

“As much as I love the show,” Pulitzer Prize-winning Los Angeles Times television columnist Howard Rosenberg says, “the ratings are the commercial equivalent of nobody’s watching, an estimated 2.5 million viewers per night. I don’t know whether the broad cross-section of viewers doesn’t want a newscast like that, or we’re so accustomed to what we’re getting now, that any story longer than 90 seconds makes us very fidgety and nervous. But the demographics are excellent, and I would assume the audience is very well-educated and influential. The people who watch are probably the people who vote.”

Education notwithstanding, some of these same people don’t seem to watch carefully enough. MacNeil and Lehrer get mistaken for each other more often than Laurel did for Hardy.

Here’s what MacNeil says about being confused with Lehrer:

“There is a fierce loyalty to NewsHour. I’ve just been off on a book-signing tour, and I got an enormous reaction. Some of them may think I’m Jim Lehrer, but that’s okay. I was at the New York Public Library, and one woman came up to me and said, ‘I just love your show. I count on it every evening.’ Finally, I couldn’t stand it any longer, and I said, ‘You know, I haven’t been on for three years.’ She looked dumbfounded and said, ‘Aren’t you Mr. Lehrer?’”

Here’s what Lehrer says about being confused with MacNeil:

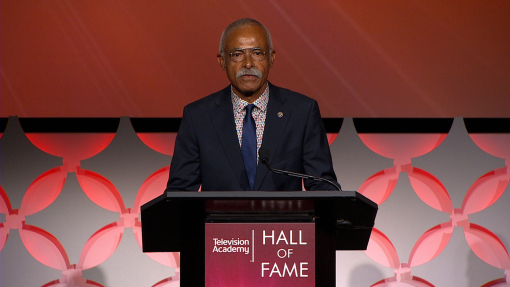

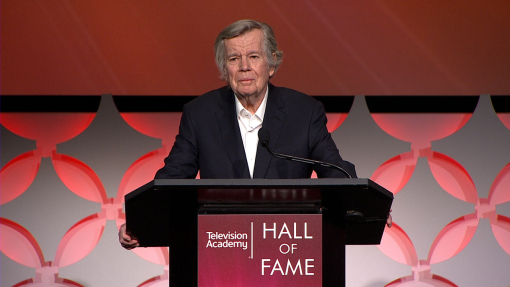

“If there was ever a person who deserved to be in the Television Hall of Fame, it’s Robert MacNeil. There is nobody, in my opinion, who has made a larger impact on proving that a serious approach to news works and can be successful in the marketplace. He deserves every award, every recognition there can be. My own role has been his helper, and I’m honored to be included with him. People still get us confused, and always will, and that’s just fine with me.”

For those still mixed-up, despite the pair’s leviathan 20 on-air years together at PBS, Lehrer is the one who’s still on. It hasn’t been the MacNeil/Lehrer Report since MacNeil retired to write books, full-time, following heart problems, in 1995. (If you haven’t noticed, it’s now the Jim Lehrer NewsHour.) Lehrer is the ex-Marine, newspaper city editor from Wichita, Kansas. MacNeil is the Halifax, Nova Scotia-born son of a mountie, who missed a career in the Canadian Navy because he flunked algebra. Lehrer is the guy whose wife, Kate, and three daughters — Jaime, Lucy, and Amanda — are also prolific, published writers. MacNeil is the husband of Donna, father of dancer Cathy, set designer Ian, social worker Alison, and film editor Will.

Besides, Lehrer’s hair is darker. To distinguish them further …

Robert MacNeil came from a long line of Bobs — at least two, his father and grandfather — so his mother, Peggy, referred to him as Robin. As has just about everyone since. (She loved Christopher Robin in Winnie the Pooh, and claimed that a robin perched on her windowsill when her son was born.) MacNeil’s book Word Struck recounts falling in love with books and words, there in Halifax. Seems his mother read to him, along with brothers Hugh and Michael, “extravagantly” during World War II, when their father was away fighting the Germans in the North Atlantic as a commander in the Canadian Navy. A diet of Dickens, Stevenson, A.A. Milne, plus “rather strict” Canadian schools led young Robin to the conviction that “good grammar was much closer to Godliness than cleanliness.”

“And I’m one of those people,” the 68-year-old MacNeil added, from his home in Manhattan, “who is forever stamped by the Depression. You’ll find this with Jim Lehrer, too. It’s a degree of caution, and a little of you can’t believe the good times are going to last, so you’d better be careful.”

After the Navy dreams went up in a puff of quadratic equations, MacNeil enrolled in Dil-Housie University and acted in Shakespeare plays, only to be promptly recruited for radio acting by a CBC producer. “Naturally, that made me think I was going to be a great actor,” he recalled. He played a lazy farm boy with a rural twang on a radio soap (“the comic relief”) before dropping out of college and working full-time as an all-night disc jockey for a year at a local pop station. “I was a most unlikely person for this because I knew a lot of classical music and couldn’t have cared less about Les Brown and His Band of Renown.” Then came a couple hard-knock years trying to make it as an actor, landing him in New York in the fall of 1952, dependent on $67 in his pocket and a charitable girlfriend.

“One day, I had an epiphany crossing Times Square,” he remembered. “A voice spoke to me out of the blue. It sounded like the voice of God to me, only I don’t believe in God. It said, ‘You’d make a terrible actor. You’re meant to be a writer, the cool one, behind the scenes.’ And I believed it. It’s the clearest thing that’s ever happened to me. I said to myself, ‘Well, if you’re going to be a writer, you’ll need more education.’ So I borrowed bus fare and went back to college in Canada.”

Three years later, he was graduated with a B.A. from Carleton College in English, with his heart set on writing plays. Thinking London was the “fountainhead,” MacNeil simply saved up and moved there, where, in time, he “nearly got a play produced, but not nearly enough.” How and why did this esteemed journalist get started in his illustrious career? Pragmatically. He joined Reuters’ London bureau to earn a living and support his (first) wife. After five years (and still no plays produced), he springboarded to NBC as a weekend back-up to London correspondent John Chancellor.

Jim Lehrer got his start in journalism by way of second base. “In high school, I wanted to be a professional baseball player, where I dreamed of bringing new art to turning the double play, but realized I wasn’t good enough,” he said, reached at his office (liberally decorated with bus driver hats, depot signs, etc.). “I became intrigued with sportswriters coming to our games and decided that would be a great thing to be. I had also written a theme on Charles Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities. My teacher had given me an A-plus, and she had written in the corner, ‘Jimmy, you’re a very good writer.’ So those two things came together, and I never looked back.”

He also never looked forward to a career in television. His first boyhood love, even more than baseball, was a bus, courtesy of his dad, Fred, who worked for Trailways buses, and ran his own ill-fated busline for a brief time (the subject of Lehrer’s 1975 book, We Were Dreamers). His second love was reading. At home his mom, Lois, read incessantly, and her habit caught on with Fred, Jr., and Jim. Encouraged by Mom and that high school English teacher, young Jim became editor of his high school paper, and later, while earning a B.A. in journalism from the University of Missouri, his college paper, all the while supporting himself by working nights at the local Trailways depot. Following tradition set by his father and brother, he next joined the U.S. Marines, serving as an infantry officer from 1956 to 1959 before returning to civilian life as a reporter for the Dallas Morning News. It was then that two important figures changed his life: one literary, and the other a young woman in love with literature.

“I had just finished reading Ulysses. I had read it on my own, without any notes or anything,” Kate Lehrer once reminisced, of her first meeting with Lehrer, a neighbor in her apartment building. “And Jim had read it the year before, using one of those guides. And I was really impressed. It was years before he told me why he had caught all that.”

Their courtship was as succinct as Ulysses wasn’t. It was two weeks before Lehrer proposed, and about six months before they married. At 38 years together, they’re compensating for the whirlwind courtship.

Lehrer soon moved to the Dallas Times-Herald, and into an ironic bit of history, on November 22, 1963. It had been raining, but was clearing up. The young reporter was at Love Field that morning, on the phone to his rewrite man, who asked if the Kennedys’ Lincoln was going to use the protective bubbletop in the motorcade. Dutifully, Lehrer walked to where the motorcade cars waited, and asked a Secret Service agent. That agent got on the radio to other agents, and asked if it was dry downtown. The answer: yes. The decision: no bubbletop. That night, amid the mayhem that followed the assassination, Lehrer was approached by the agent he had spoken with that morning. “God,” said the agent, “if I just hadn’t taken off that bubbletop.”

Lehrer eventually became city editor of the Times-Herald, although his heart was set on loftier verbal pursuits. In his spare time he had scratched out a comic screenplay about retaking the Alamo, called Viva Max! Lo and behold, it sold. Lehrer pocketed $45,000 and walked away from newspapers forever. “I figured,” he said, “we could live for four years on that. I had been working 12 hours a day, and I wanted to be a writer, so I quit.”

How Lehrer met MacNeil has a lot to do with the way they both met public television. Soon distracted from his writing idyll to consult for a public TV station in Dallas, Lehrer found himself composing a proposal for a Ford Foundation grant to do an experimental TV news program, “a kind of newspaper on the air.” He got it, the show worked, and “next thing I knew, I was in Washington” (as PBS public affairs correspondent).

MacNeil’s path to PBS was comparatively rollicking, and helped cost him, he said, his first two marriages. While NBC’s number-two correspondent in London, he found himself on assignment in Germany one morning, at the moment that the first bricks of the Berlin Wall went up at the Brandenburg Gate. Not long after, he was sent to Cuba to cover the missile crisis because he had a Canadian passport and wound up locked in a hotel with other correspondents, under guard.

“I was sweating it, for a few days,” he said. “The American planes were coming in very low, and we thought the place was going to get bombed. We were forced guests for nine days. Then we were let out, and I was arrested again, sent to jail for a few days, and deported. The main thing I got out of that, besides a lot of colorful stories, was a box of cigars that I gave to correspondent Sander Vanocur, who gave it to press secretary Pierre Salinger, who gave it to President John Kennedy. So Kennedy got a box of Cuban cigars from the Cuban war.”

In Dallas, moments after the Kennedy assassination, MacNeil ran into a guy coming out of the Texas School Book Depository and asked him if there was a phone inside. The guy, in all probability, was Lee Harvey Oswald. (MacNeil later wrote a book about all these things, The Right Place at the Right Time.) A roving feature reporter for The Huntley-Brinkley Report at NBC until 1967 (a job he loved), the man bolted when they tried to make him sit in the weekend anchor chair. (“I felt fraudulent doing it”). He went to the BBC in London and joined a (still-running) British TV news magazine called Panorama, then back to the states to cover the 1972 elections on loan from BBC for PBS, with old Cuban jailmate Vanocur.

“We got a lot of flak from the Nixon Administration,” he said, bitterness still in his voice. “There were memos from Bob Haldeman saying, ‘We’ve got to get rid of these guys or they’ll start another liberal network,’ or something. They spread all kinds of stories about us at public television, and it was really bad. At the end of the year, Sandy left because he was much better known than I was, and was the target for much of this.”

Vanocur was replaced by a guy named Lehrer, and within two months, the pair was covering Watergate almost around the clock, for 47 straight days and nights. Clamoring for a nightly MacNeil/Lehrer show ensued, but Jim stayed in Washington and Robin returned to London. But after two years of badgering from WNET in New York, MacNeil caved in. The MacNeil/Lehrer Report (at first oddly named the Robert MacNeil Report, with Jim Lehrer) debuted in 1975, with Lehrer in D.C., and MacNeil in the Big Apple. From then until 1983, each half-hour program luxuriously, impossibly, focused on a single issue.

“Jim Lehrer and I had become instant good friends,” said MacNeil. “I mean, we really are each other’s closest friends. The Report became an institution amazingly rapidly because we had fitted into a niche right after the network news shows in a kind of dead half-hour of network time. We used to advertise, ‘Watch Walter Cronkite, then Watch Us.’”

In 1983, they went to the full NewsHour, becoming what critic Rosenberg calls “the bow-tie of TV news.” “They were,” Rosenberg said, “far and away, hands down, any cliché you want, the best newscast on TV. It’s not even close. Lehrer is carrying on very well. He’s very thoughtful. What I really adore is the historical perspective, the way they analyze the story, especially now in this time when everyone has a knee-jerk reaction to what’s happening vis-a-vis Clinton and the impeachment. At least twice a week, Lehrer gathers other commentators together and they discuss the issues with real historical perspective. They don’t argue, as on Crossfire; they don’t spit and call each other sluts and whores. They relate things to the past, which is so important in journalism today, when so many of us in the media are amnesiacs, recreating the world every day from scratch, with nothing to connect the present to the past.”

The bow-tie has not always been perfectly straight, of course — like the in-studio segment they once did on the supposedly flavorless “plastic tomato,” a year-round genetically engineered thing that smelled so delicious that MacNeil had trouble keeping a straight face. Or the occasional petrified guest, like the expert on a series of grain elevator fires. “This guy froze up!” said MacNeil. “I read the introduction, and he went catatonic. He stared at me, glassy-eyed! So I gave some more background, and he was still absolutely stiff like someone had injected him with strychnine.”

“Whenever television is depicted in the movies, or even in television itself,” said MacNeil, “it’s always full of tension and radical shouting. Do this! Take three! This kind of thing. Actually, it’s like being on a movie set. It’s extremely work-a-day quiet and concentrated and undemonstrative. It’s like building brick walls every day. You put the bricks in place, you hope they’re straight and don’t fall down.”

Lehrer, of course, now supervises building of that wall alone, a sober, confining task that he describes as “the ultimate freedom.”

“Garrison Keillor said, ‘You know, you want to entertain people, you’re gonna have to compete with Frank Sinatra CDs,”’ laughed Lehrer. “If you want to have fun, don’t watch the news — go to the circus. I’m in the information business. I’m able to spend 100 percent of my time on the editorial matters at The NewsHour. Nobody tells me what I can do and what I can’t do. You ever watch our program and you don’t like it some night, blame it on me. I’m fully responsible. I can’t ever say, ‘Well, they made me do this.’ It’s the best journalism job, not just on television, but in the country. No question about it.”

Added MacNeil, on Lehrer:

“He has inherited the Walter Cronkite mantle as the most trusted man in America.”

Added Lehrer on MacNeil:

“This is something Robin MacNeil created 23 years ago, and I was there to help him. And I am able to bear the fruit.”

This tribute originally appeared in the Television Academy Hall of Fame program celebrating Robert MacNeil and Jim Lehrer's induction in 1999.