For more years than he might care to remember, Leonard Harry Goldenson was the television industry’s stepchild: hardworking and tolerated, but mildly disdained and certainly not loved. As head of the network that always ran behind CBS and NBC in advertising, ratings, and earnings, Goldenson was invariably viewed as the least powerful member of the broadcasting triumvirate that included NBC’s David Sarnoff and CBS’s William Paley.

Indeed, Goldenson and his American Broadcasting Company existed on the outer edges of power until only a decade ago, when he became architect of one of the most spectacular turnarounds in business history. In 1976, ABC-TV, the perennial also-ran, suddenly rose to the top of the ratings charts. It was about that time the network began to call itself “the world’s largest advertising medium.”

Many observers, of course, regarded ABC’s triumph as a fluke. But when the network continued its winning streak to 1977 and 1978, the doubters became believers. By 1979, Fortune magazine was citing ABC’s accomplishment as one of the most noteworthy business achievements in 20th century America. Dun's Review hailed the network as one of the five best-managed companies in the nation. And Goldenson, ABC’s longtime chairman, the man who refused to let his company die, stood in the center of it all, vindicated at last. The stepchild had become the golden son of the industry.

But the triumph that made “little ABC" a broadcasting powerhouse began before 1976. In general, broadcast historians agree ABC’s climb from relative obscurity began in 1953, when it merged with the United Paramount Theaters to avoid bankruptcy.

Goldenson’s story, however, is more than a single spectacular triumph, more than a record of increased earnings and a series of ratings victories. His story belongs to the early history of American television, and it begins in 1933, when Goldenson reorganized Paramount Pictures’ troubled New England theaters into profitable ventures.

A young, ambitious attorney with two Harvard degrees, Goldenson had been reared in a small western Pennsylvania town called Scottdale. Born there on December 7, 1905, he grew up surrounded by movies, largely because his father, a clothing store owner, had a side interest in the local movie theater.

It was therefore fitting that his professional life should begin with movies. The reorganization of Paramount’s New England theaters took him four years, during which he learned all he could about the theater business. He spent his days making the theaters a financial success; he spent his nights going into the movie houses and talking with personnel. In 1938, after a period of troubleshooting for Paramount’s other properties, he was assigned full responsibility for the studio’s 1700 theaters.

He rose quickly through the Paramount ranks: a vice-president in 1942, a director in 1944. In 1950, after movie studios were required by federal antitrust decree to separate from their theater operations, Goldenson was elevated to the presidency of the newly created United Paramount Theaters. It was in this position that he engineered the merger of United Paramount and ABC.

“I felt television had a great future,” Goldenson recalls. Paramount already owned one of America’s first commercial TV stations (WBKB-TV in Chicago), which provided Goldenson with a firsthand look at television’s potential. His assessments led him to actively pursue the merger between the faltering ABC network and the largest movie theater chain in the nation. (ABC was founded in 1943 as an offshoot of the old NBC blue network.)

After the merger received the FCC’s stamp of approval, Goldenson was named president of the new American Broadcasting-United Paramount Theaters. Afterward, journalists liked to refer to him as “the man who wed television to the movies.”

Goldenson presided over a company that owned (by then) 1600 movie theaters, a strong radio network, radio and TV stations in five cities, and, most importantly, all 14 affiliates of its TV network. Goldenson’s entry into the television arena constituted the beginning of a herculean effort, a 23-year battle to achieve parity with CBS and NBC.

He started that effort with a fairly large bang: he, the movie veteran, seduced Hollywood. “The motion picture business was fighting television,” he recalls. "At the time, ABC had no talent, really. All the talent was on CBS and NBC. They had the Bennys, the Hopes, the Godfreys, the Berles. All ABC had was Ozzie and Harriet. My position was we had to go to Hollywood to bring Hollywood to television.

Earlier he had attempted to interest Walt Disney in providing a series for what would be the new ABC-TV. But Disney wasn’t interested until he needed a way to finance an amusement park that would ultimately be called Disneyland. It was then that Walt’s brother Roy, the Disney studio’s business manager, was dispatched to New York to convince a network to underwrite the amusement park. After CBS and NBC turned him down, Roy phoned Goldenson

“Leonard, a couple of years ago you expressed an interest in working out something with us in television,” Roy began. “Are you still interested?”

“Roy, where are you?” Goldenson asked. Disney named the hotel, to which Goldenson replied, “I’ll be right over.”

ABC’s deal stipulated, among other things, that the Disney studio would supply a one-hour television series to the network in return for a $500,000 investment in Disneyland park. Paying $50,000 per program, ABC would own 35 percent of Disneyland and guarantee loans up to $4.5 million. Thus, ABC was able to telecast a show that enhanced its effort to be taken seriously.

Disneyland, the show, aired October 27, 1954, and went on to become ABC's first major hit series. It marked the first time a Hollywood movie studio ventured into television programming.

With Disney in his camp, Goldenson convinced Warner Bros. to provide programing for ABC. One of that studio’s entries, Cheyenne, emerged as one of the most popular shows of the 1955-56 season. An ABC staple, it played another seven seasons and helped launch a TV westerns trend that continued for two decades.

Goldenson’s deal with the Warner studio “was considered far more momentous than the Disney contract because Warner Bros. was one of the ‘majors’ — the aristocracy,’’ writes broadcast historian Erik Barnouw in Tube of Plenty.

Fortunately for ABC, neither NBC nor CBS was “interested in movies at the time,” Goldenson remembers. “As a matter of fact, Sarnoff once said to me, ‘What are you going to do for programming?’

“I said, ‘I’m going to go to Hollywood.’

“And he said, ‘Hollywood? This is a medium of spontaneity, not of film.’”

“I said, ‘It doesn’t make any difference, as long as you entertain the public.’”

Another programming milestone, ABC’s Wide World of Sports (first aired in 1961), helped establish the network as the leading sports medium of the time.

In 1966, Goldenson, seeking to strengthen the network with a large infusion of cash, sought ABC’s merger with International Telephone & Telegraph Corporation. Although the FCC approved the merger by a vote of 4 to 3, the Justice Department asked the U.S. Court of Appeals to forbid it on the grounds that ABC’s journalistic independence could not be protected. Faced with delays and litigation, ITT withdrew, and the merger prospects collapsed in 1968.

Although Goldenson had sought the merger, ABC ultimately was paralyzed by it. “It tied us up for two years,” Goldenson admits. “We couldn’t do anything." The network couldn’t borrow any money beyond $25 million — this during the era when color was coming to television. “That’s one of the reasons I was interested in the merger with ITT," Goldenson explains. “We needed the money to convert to color.”

ABC also needed an infusion of $120 million in cash to compete with CBS and NBC, both of which by that time were programming not just one, but two nights of movies, according to Goldenson.

But before he could make an assault on the other networks, Goldenson faced another formidable adversary in Howard Hughes, who attempted to take over ABC. In a shrewd move broadcasting observers still like to talk about, Goldenson thwarted the takeover by forcing a court action that would have required the reclusive billionaire to make a personal appearance before the FCC. Rather than appear in public, Hughes dropped his takeover attempt.

With the Hughes matter out of the way, Goldenson, who was elected chairman and chief executive officer in 1972, began to build a top-notch management team. Through that team, which included Fred Silverman as programming chief, the chairman launched a more concerted effort to reach the 18-49 age group.

“CBS and NBC had an old-age bias," Goldenson says, “but we went after the young families of America, because they more readily switched their dials to something new.” Going after the younger market had been an ABC policy since the late 1950s, according to Goldenson. In the early 1970s, that effort shifted into high gear.

ABC-TV chalked up its first profit in more than a decade in 1972, making it the primary contributor to the American Broadcasting Companies’ record revenues of $869.4 million, up 15 percent from 1971, with net earnings of $35 million, up more than 50 percent.

By 1973, with its spectacular coverage of the previous year’s Munich Olympics still reverberating throughout the industry, the network began its gallop to narrow the ratings between itself and the CBS/NBC Goliath.

The team Goldenson built finally hit the jackpot in 1976. “In the swiftest and most unnerving shake-up in television history, ABC, the perennial last-place network, shot past NBC and toppled CBS’s 20-year dominance in the industry.” That’s how Women’s Wear Daily described ABC’s streak to the finish line.

ABC continued its gallop as number one in ratings and advertising well into the 1980s.

The American Broadcasting Company relinquished its theater holdings in the early 1970s. Today its interests include the ABC Broadcast Group, the company’s largest operating entity; ABC Publishing; and ABC Video Enterprises.

On June 25, 1985, Goldenson, then 79, presided over his final stockholders’ meeting in New York and handed ABC’s reins to Capital Cities. He had wanted Capital Cities as a merger partner because he was comfortable with the company’s philosophy and because he wished to prevent ABC from becoming the target of a hostile takeover bid either before or after his retirement.

“Having built this empire worldwide, I didn’t want it to be dismembered,” explains Goldenson, now chairman of the executive committee of Capital Cities/ABC.

The man who had devoted a lifetime to building ABC into a global communications giant was philosophical on his final day at the helm:

Return with me for a moment to a different time in the history of our company. When I first addressed an annual meeting of ABC shareholders in 1953, ABC had just completed its first merger. The company was a newly formed combination of radio, television, and motion-picture theater operations. We were determined to build a future as a great broadcasting company. Today, that early vision has been realized.

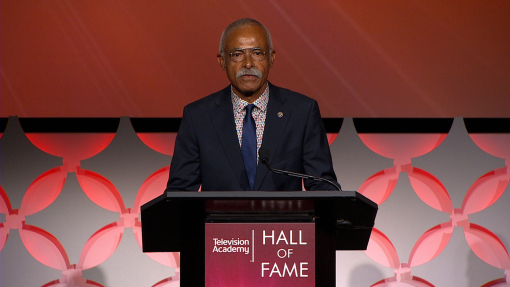

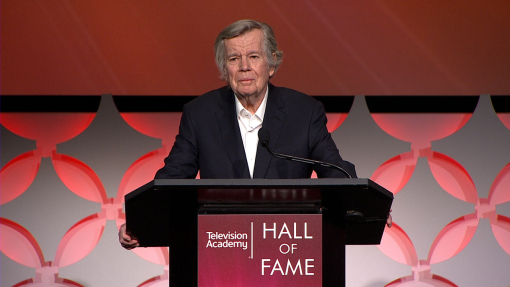

This tribute originally appeared in the Television Academy Hall of Fame program celebrating Leonard Goldenson’s induction in 1987.