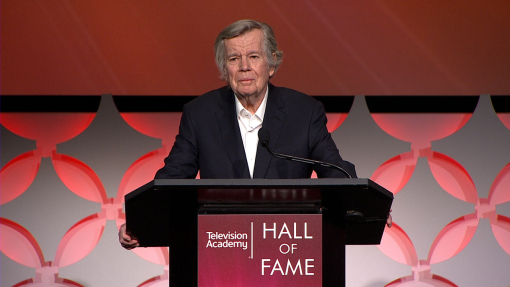

Jim McKay took the Wide World of Sports and turned it into a small town. No sportscaster in history has done more to transform contests as traditional as track and field, or as esoteric as the gymnastics balance beam, into palpable and immediate events — events that can make anyone with a can of beer and a TV set stand up and shout, or shed a tear.

McKay — who will observe his 50th anniversary in television in 1997 — brought to his craft an almost impossible combination of news reporting skills, geniality, and a knack for making things understandable even to the sporting illiterate. In a profession rife with wacky personalities and dull ex-jocks who have trouble making nouns and verbs agree, McKay is the sportscasting equivalent of Lord Byron.

He humanized the competitions he covered — including 11 Olympic Games — to such an extent that you often ended up rooting for … everybody. The importance of this cannot be overstated, particularly in the context of the Cold War — a time when many U.S. citizens had trouble understanding that nice kids dreamed of winning decathlons in the Soviet Union and China, too. McKay's ever-informative anchoring of ABC's Wide World of Sports has reminded for 34 years that the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat are not confined to Toledo and Podunk.

Quoth Los Angeles Times sports columnist Mike Downey:

Like a great tour guide, Jim McKay sat in the front of the bus and took us all over the world. He was like the Charles Kuralt of sports. I never thought that Jim McKay labored too much to be too funny, too clever, too pompous. He was always the voice of reason. You didn't sense an ounce of xenophobia; he was someone who was jingoistic about the American teams, but was perfectly willing to tell you if Valeri Borzov or a great Russian sprinter was the best in the world. He could admire what Borzov was doing every bit as much as he could admire what Carl Lewis was doing. I think he had a dignity about him that television lacked in a lot of other sporting events.

Like Walter Cronkite, McKay is one of those rare television figures who comes across as a person in your living room — not an image in an electronic box in your living room. His longtime colleague and friend at Wide World of Sports, producer Dennis Lewin, likened the man to a best friend, uncle, or grandfather sitting on the sofa next to you — "explaining all the nuances of what you were watching, and telling you about all these wonderful people and places he knew.

“There was never any artifice with McKay, no phony ‘broadcaster's voice,’ not even requisite sportscasting signature clichés like ‘whoa, Nellie!’ or ‘from DOWN-towwwwnnn …’ You could just turn on the tube every Saturday afternoon and listen to this amiable guy tell you — articulately, and with genuine excitement — the stories behind the people who were launching that big iron ball, or who had developed a new reverse style for the high-jump, or who were battling asthma as well as the hundred-meter hurdles, or who took off just a little too early on that ski-jump.

"It was always ABC sports style, and continues to be to this day," Lewin continued, "to focus as much on the humans that participate in sports as much as the sports themselves. It's a style that really evolved out of Wide World of Sports, and it's a style that Jim McKay brought to perfection."

It's a style that also has been mighty good for sports. McKay's reportage not only helped to put more people in the stands — it ultimately helped put more players on the field, and on the mat, and in the pool, and on the slopes, and in the rink …

"In the early 1960s," Lewin remembered, “you couldn't fill local figure skating arenas for national competitions, and now they're getting as much primetime exposure as almost any other sport! The reality is that they were really put on the map by Wide World of Sports in general and Jim McKay in particular. When you think back to the great names in gymnastics and figure skating, they're inexorably linked with Jim. When you think about Olga Korbut in gymnastics, when you think about Peggy Fleming and Dorothy Hamill in figure skating, inevitably the name you link with them is Jim McKay.

The name that Jim McKay inevitably links with them is Jim McManus. It's a name inevitably linked to him — on his birth certificate. Yes, McKay is not his given name. It's kind of a long story, and it begins back in 1950 …

McKay was hosting a three-hour TV variety show called The Sports Parade in Baltimore — emceeing the first and third hour, and directing the second. The program indeed featured sports news — tucked between interviews with "everybody who came through town: politicians, singers, dancers." It even featured McKay — McManus, then — singing! That's right — there's a little of the Irish tenor in him; the family lineage goes back to County Armagh in Ireland. (He patterned himself after his idol of the time, Bing Crosby.) McKay picks up the action:

“One day I came out of the studio and the general manager was standing there with a guy who was right out of a Hollywood movie. He was short and stocky, he had black hair combed straight back over his head and a big cigar in his mouth. The general manager said, ‘Jim, I'd like you to meet Mr. Dick Swift from CBS in New York!’ Whereupon the guy said, right out of that Hollywood movie, ‘Hiya, kid.’ How would you like to do something like this in New York?”

Swift came from a radio background, where a single name could be invented and trademarked for use by different announcers at different stations within a network (figure that one), and decided to re-christen McManus in order to call his New York CBS variety show (cough, sputter) "The Real McKay." (Yes, he sang there, too.) Said Jim: "This was the big chance to go to New York, so I wasn't going to argue with them ... In all normal social dealings with friends, it's still McManus. I think McManus. McKay — it's served a certain purpose."

So did the Philadelphia Athletics baseball team — even if it wasn't to inspire their fans. The Philly-born McKay credits the losing proclivity of his hometown A’s, and their impact on a certain well-known sports-writer, with instigating part of his career ambition:

"I've been a sports nut all my life," said McKay, who from age 12 yearned to either become a newspaper reporter or get into radio sports announcing (there was no TV at the time.):

“I lived in Philadelphia till I was 15, so I was a fan of the A's. We were always last, but I never gave up! There was an old paper called the Philadelphia Record, and there was a young guy who was covering the A's. Well, they were in last place again, and it struck me that despite this, every day of the 154-game season, this guy either wrote an interesting or funny story — and did it so well that it held your interest. I thought, I'd like to be able to do that! As it turns out, his name was Red Smith [one of the most revered of all sports scribes]. He became a friend later, which was another of those impossible goals I've been lucky enough to fulfill.”

The broadcasting part of McKay's career ambition came from radio sports announcer Ted Husing: "I loved the way he talked," McKay said, speaking by phone from his pastoral thoroughbred horse farm in Monkton, Maryland. “He had mellifluous tones, and he was not averse to using a three-syllable word if he thought it would make the story better than a one-syllable word — or vice versa. So I thought he was outstanding and I'd try to imitate his voice. When I wasn't imitating Bing Crosby, that is.”

The next part of this story can be filed under Any opportunity is a good opportunity, or You never know. After moving to Baltimore, McKay wrote a little high school sports column — for a local ladies' magazine (!) called Gardens, Houses, and People. (His pay was an annual Christmas tie.) He was a bit embarrassed about it, but his father encouraged him to persevere. Later, coming home after a three-year stint in the Navy as captain of a minesweeper in the South Atlantic ("I thought the people back home were getting all the good jobs in TV and radio and I'd never have a chance"), McKay found himself kicking around Baltimore, looking futilely for work. The president of his alma mater, Baltimore Loyola College, put in a good word for the newly discharged young naval officer at the Baltimore Evening Sun.

“I came down for an interview and the city editor said in the course of conversation, ‘Are you by any chance the Jim McManus who wrote a column for a little local magazine called Gardens, Houses, and People about high school sports?’ I said, ‘Yes,’ and he said, ‘I thought that was some of the best writing in town.’” That's how I got the job.

McKay went to work — writing news — for city editor Ed Young, who soon "taught me everything about reporting that I know." That hard news print-journalism experience proved invaluable (most notably 25 years later when McKay found himself handling international coverage of one of the most despicable events in sports history: the terrorist killing of members of Israel's 1972 Olympics team). Two years into his job as a newsman, the Evening Sun acquired one of those new-fangled TV stations. For some reason, management collared three reporters to run the thing. McKay, a college English literature major who had also been quite the campus thespian (a "wonderful actor" who essayed principal roles in several school plays, including George Washington and a Pope, according to wife Margaret), was a shoo-in for TV, as far as management was concerned.

"They said, 'We want to go on the air next week and we have all the cameras and technicians, but we don't have any producers, directors, or announcers, and you guys are going to be it,"' McKay laughed. "And I said — you know the old line, 'Why me?' They said, 'Well, did you say you were the president of the dramatic society at Loyola College?' I said 'Yeah.' They said, 'Well, that's good enough.'"

So, on the strength of a resume that was based largely on a gardening magazine column and having portrayed the Pope in a school play, McKay wound up becoming the first voice on Baltimore television on November 5, 1947. In short order, the fledgling announcer was hosting a three-hour afternoon program that often closed with him crooning things like "The Same Old Shilelagh My Father Brought From Ireland."

McKay's television sports reporting debut came three years later on the New York show arranged by Swift. It took the form of a five-minute wrap-up on the CBS 11 p.m. news, and promptly led to a few network assignments in golf and horse racing. The man became a sportscasting fixture at CBS for the next 10 years — until, while covering the Masters Gold Tournament in 1961, a phone call came from two guys named Roone Arledge and Chet Simmons. Seems they were starting an ABC weekly program called World of Sports. It debuted, with McKay at the helm, as a summer replacement, returning the following January with "Wide" attached to the title.

"At the beginning," said McKay, we had to be educators as well as reporters, because a lot of the sports we did were not familiar to the average American. I mean, very few people knew that 6.0 was a perfect mark in figure skating. Every time we did such an event, we explained it over and over, and through the years, the American sports public has become so expert that we talk to them as equals now. I think that's the biggest change in sports commentary.”

McKay himself is arguably one of the biggest changes in sports commentary. He became the first sportscaster ever to win an Emmy, in 1968, and he has since added 12 more — including one in 1988 for writing the openings of ABC Sports' coverage of the 1987 Indianapolis 500, the British Open, and the Kentucky Derby. As a result, he is the only broadcaster to have won Emmys for sports broadcasting and writing — and, of course, for news reporting. The last award came for his marathon live anchoring of the so-called "Black September" massacre of Israel's athletes at the Olympic village in Munich, Germany, in 1972. To this day, people stop him at the supermarket to say things like "I'll never forget that terrible day in Munich, and the job you did."

"It was supposed to be my day off during the Games," McKay remembered. I was going to drive my wife up into the Alps and have a pleasant day. Instead, the phone ran at six in the morning, and [I was told] ‘Terrorists have broken into the Israeli team headquarters. They've already killed one man, and they're threatening to kill others.’ We had just closed down our operation about an hour or so earlier.

Awaiting further instructions, McKay ducked out for a swim and sauna at the hotel — only to have the sauna interrupted by a knock at the door, and word that ABC Sports chief Arledge was planning to go on the air imminently. In a few minutes, the kid from Philly who had dreamed of becoming a radio sportscaster sat down to do about 16 straight hours of extremely difficult news reporting — live, updating the entire world. Cronkite couldn't have done it better.

"I remember being very aware that there was a young guy who was, I believe, a weightlifter on the Israeli team," he said. “But he was actually from Shaker Heights, Ohio. And I kept on my mind all that day that I'm going to have to be the guy that tells those people in Ohio whether their son is alive or dead, so we'd better be right, and we'd better not jump the gun. As it turns out, he was killed.”

It was difficult for McKay to remain composed.

"Nowadays," he said, “we've become almost accustomed to such things, but at that time it was such an incredible shock to everybody in the world — plus the fact that it happened in conjunction with the Olympic Games, which are supposed to be about peace and fellowship ... I was very affected by it, and I think everybody in the studio was. I've always felt in that sort of situation that there is a responsibility to allow a 'professional amount of emotion' to come through, so that people know what it is like to be there.”

There is an absurd postscript to that horrible and dramatic day. McKay's old newsman's reflexes had kicked in with such force that "it was only when I came back after the whole long day to our hotel that I realized I still had my damp bathing suit on under my pants." He was awarded the West German Officer's Cross of the Legion of Merit for his work that day, and also the George Polk Memorial Award for Journalism, of which he is particularly proud (only one is given annually in network television).

These days, aside from his familiar post at WWOS, the former Philly A's fan is a minority owner of the Baltimore Orioles (along with Margaret) — "something I never could have dreamed of as a kid." He's also a member of The Jockey Club, the governing body of horse racing in America, and founder of "The Maryland Million," a million-dollar day of racing for Maryland-sired thoroughbreds (a McKay-raised two-year-old won in the event's second year). The McKays have a son, Sean McManus, a senior vice-president of Trans-World International; a daughter, Mrs. Charles Fontelieu, is a counselor in alcohol and drug addiction; and a grandson, James.

And there is one more noteworthy point of pride in the man's life that should not be neglected here. Two years ago, he and Margaret organized a benefit concert for Loyola College, and a singer who used to be called Jim McManus got up and ventured a duet with Vic Damone. They sang "It Had To Be You." Thrill of a lifetime, was it?

"It was another one, yeah," said Jim McKay.

This tribute originally appeared in the Television Academy Hall of Fame program celebrating Jim McKay's induction in 1995.