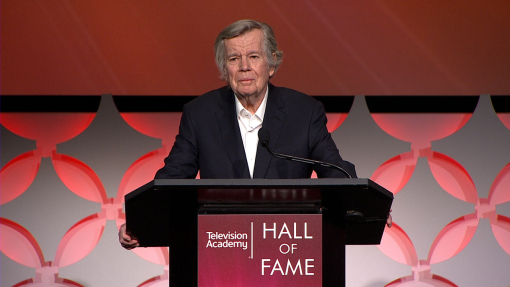

He has been called the Statesman of Broadcasting, largely because he was the industry’s leading spokesman at the White House, on Capitol Hill, and at FCC hearings. He was, above all, the industry’s foremost champion in its battle to enlarge and maintain hard-won freedoms in television communications.

Analytical, unflappable, precise, highly organized, and gifted with a sense of style and high standards, Frank Stanton, the longtime president of CBS, “was much more than a lobbyist in his public role,” according to CBS founder William S. Paley. Stanton not only thoroughly prepared for his public appearances, but also “spoke from deep knowledge and keen insight upon virtually all aspects of broadcasting and its role in a free society,” Paley has noted.

In 1948, in one of his most famous appearances before the FCC, he helped broadcasters win the right to editorialize on the air.

In 1959, he helped to persuade Congress to ease the impractical limitations of Section 315 of the Communications Act that required broadcasters to give “equal opportunities” on air to all opposing political candidates.

In 1971, he flatly refused to cooperate with a special congressional subcommittee that demanded “all film, work prints, and outtakes” accrued in producing CBS’s documentary The Selling of the Pentagon. His refusal led the full committee to cite him and CBS for contempt of Congress. But, with the First Amendment as his weapon, Stanton stood his ground and eventually won. Thus, a serious setback to free speech in this country was averted when the contempt citation was later rejected by the House.

Broadcasting’s premier spokesman was born in Muskegon, Michigan, on March 20, 1908, the first of two sons of a public school teacher and his wife. He grew up in Dayton, Ohio, graduated from Steele High School in that city, and entered Ohio Wesleyan University, where he majored in zoology. After earning his bachelor’s degree in 1930, he went directly to Ohio State University to complete graduate work in psychology, receiving his master’s in 1932 and his PhD. in 1935.

It was his doctorate thesis, a statistical paper showing that man’s ears were more effective than his eyes in absorbing information, that opened the door to his career at CBS.

In the course of his research, Stanton had requested data from CBS officials. When the thesis was completed, he sent a copy of it to the network. His work intrigued Paul Kesten, CBS director of sales promotion, who invited the young psychologist to join CBS and eventually take over the research department.

On August 29, 1935, Stanton received this telegram from Kesten:

MONDAY OK HOPE YOU DECIDE TO COME TO CBS STOP SINCE OUR TALK SEVERAL NEW RESEARCH PROBLEMS HAVE ARISEN WHICH I THINK WOULD INTRIGUE YOU STOP I DON’T KNOW OF ANY OTHER ORGANIZATION WHERE YOUR BACKGROUND AND EXPERIENCE WOULD COUNT SO HEAVILY IN YOUR FAVOR OR WHERE YOUR TALENTS WOULD FIND SO ENTHUSIASTIC A RECEPTION.

Stanton’s rise through the network’s ranks was swift and meteoric: director of research (1938), vice-president (1942), general manager and member of the board of directors (1945).

In the 1930s, he had invented the first automatic recording device designed to be placed inside home radio receivers to record actual listening habits. During World War II, Stanton, along with Paul F. Lazarsfeld of Columbia University, developed the Stanton-Lazarsfeld program analyzer. A precursor to contemporary ratings devices, the mechanical gadget measured listener reactions to programs, songs, and movies.

On January 9, 1946, in a reorganization of the network, William Paley moved up to chairman of the board and Stanton was elected CBS president.

He had reached the top at an auspicious time in world history and CBS history; a devastating war had just ended, and a revolution called television was about to emerge as a dominant factor in American life.

As president and chief operating officer, Stanton was responsible for handling the day-to-day activities, including relations with affiliate stations and significant dealings with Congress and the FCC. He systematized company procedures and chains of command and, in 1951, oversaw the restructuring of the company into six separate and distinct operations: CBS Radio, CBS Television, CBS Laboratories, Columbia Records, Hytron Radio and Electronics, and CBS-Columbia. His purpose, he often said, was “keeping the company going.”

By the early 1960s, “keeping the company going” for Stanton meant considering other ventures, such as CBS’s earlier successful investment in Broadway’s My Fair Lady and its acquisition of the New York Yankees. Diversification, as Stanton saw it, was essential; for although CBS, Inc., which included the television network and its six subsidiaries, made nearly $50 million in profits during 1964, its growth limit was approaching. Television advertising revenues accounted for the bulk of its income. The FCC allowed a network to own only five television stations, and the number of CBS network affiliations was not likely to increase significantly within the near future. CBS, nevertheless, achieved an extraordinary position under Paley and Stanton. By 1964, according to Forbes magazine, CBS had become the largest advertising and communications medium in the world. Moreover, each of its five television stations was a leader in its own market.

And Stanton’s enormous executive abilities were always as prominent as his statesmanship.

Besides winning broadcasters the right to editorialize (which CBS network has rarely exercised) and protecting the right of free speech for broadcasters, Stanton, the statesman, has defended the CBS Vote Profile Analysis by maintaining that acquiring selected samples of national election results before all polls have closed is a legitimate reporting device.

He has also proposed a 24-hour voting day across the United States for national elections. Furthermore, in keeping with his conviction that broadcasting should be given full access to newsworthy events, he has urged Congress, the Supreme Court, and other legislative and judicial bodies to open their proceedings to television and radio reporting.

In addition, he has urged that political conventions take place in September, thereby cutting campaign time to no more than a month. He continues to propose that broadcasters in the United States and Canada establish a worldwide organization of television broadcasters to facilitate the exchange of satellite programs among continents.

“He’s brilliant, he’s a visionary, and I believe he’s courageous,” says Bob Wood, former president of CBS Network. "And that courage was exemplified in his stand on The Selling of the Pentagon issue before Congress. He set a standard so high that everyone stretched to reach it … He was a true broadcaster in that he knew all the elements that made up the industry."

“[Stanton], more than anybody, recognized [CBS] wasn’t just a business, but a business with a very special public responsibility,’’ says Dick Salant, former president of CBS News. “He was our protector and our champion.”

A winner of numerous awards, Stanton was given the Trustees Award of the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences in 1960 “for his long and outstanding efforts to win for broadcasting the same freedom of expression guaranteed to the press by the Constitution.”

He is a fellow of the American Psychological Association and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In September, 1971, Stanton left the CBS presidency and moved up to the vice-chairmanship of the board. In March 1973, on the last day of the month in which he reached age 65, he retired as vice-chairman. He continued to serve on the board for five more years and is still employed as a consultant to CBS.

This tribute originally appeared in the Television Academy Hall of Fame program celebrating Frank Stanton's induction in 1986.