Bob Schieffer started reading the newspaper as soon as he could read, and by the time he was 11, he was hooked on politics. He would check the hometown Fort Worth Star-Telegram for stories of Lyndon Johnson’s 1948 whistle-stop Senate campaign, and was there to gawk as the man who epitomized Texas politics descended from the sky in a cloud of dust onto a baseball field in a helicopter known as the Johnson City Windmill and flung his Stetson cowboy hat into the crowd.

An interest in journalism grew in ninth grade, when Schieffer won a prize for sports writing. “I don’t remember what the story was about, but I know that I beat the seniors,” he recalls, “and I remember that my byline looked fine. I think it may have been the first time I had ever seen my name printed out like that.”

The byline was Bob, not Robert. Like many sons of the south, he was named Bob at birth. His nickname was Bobo, and that’s what his three granddaughters still call him.

When Schieffer saw that byline, he says, “I knew what I wanted to do.”

He wanted to be a political reporter. But being on television was never part of the dream. Schieffer says his two daughters used to ask if he wanted to be a television reporter when he was a little boy and were surprised to learn they didn’t have television back then. He thinks he was in eighth grade when his family went out to eat one night at a Mexican restaurant next door to an appliance store. “They had a television in the window, with a tiny screen, and they were showing a movie starring Rex Harrison,” he recalls. “My dad, who was hungry, wasn’t impressed, and said ‘Let’s go eat,’ but that was the first time I saw television.”

Not long after, his family got an Admiral — “like a big piece of furniture” — and they sat around and watched Milton Berle on NBC’s Texaco Star Theater, John Daly on ABC’s What’s My Line?, John Cameron Swayze on NBC’s Camel News Caravan, and Douglas Edwards, America’s first anchorman, on the CBS Evening News.

While his friends assumed Schieffer would go into journalism, his mother wanted him to be a doctor, so he enrolled at Texas Christian University and spent two years as a pre-med major. He couldn’t ace biology with a little creative writing, so he switched to journalism in his junior year. And while he was still in college, he landed his first paying job at $1 an hour, working the night shift in the news department of radio station KXOL.

Every week of his life since then, Schieffer has been drawing a paycheck as a reporter. He was the first reporter to cover Vietnam for a Texas newspaper, and when he returned, he accepted a job with the local television station, an attractive offer because it paid $155 a week, $20 more than the $135 he had been getting at the paper.

He has always believed that CBS hired him by accident, after he walked into Bureau Chief Bill Small’s office without an appointment and said, “I’m Bob Schieffer, here to see about a job.” To his amazement, the secretary said, “Oh, yes, Bob, go on in.” It wasn’t until later, on his way out, that he saw journalist Bob Hager by the elevator, and confirmed some years later that it was Hager who had an appointment with Small that morning.

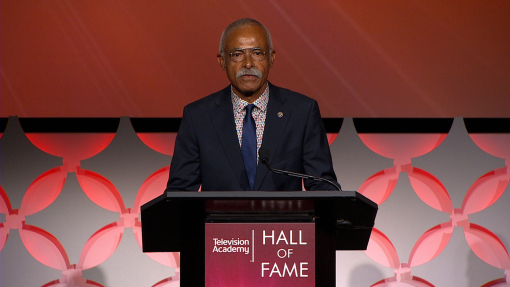

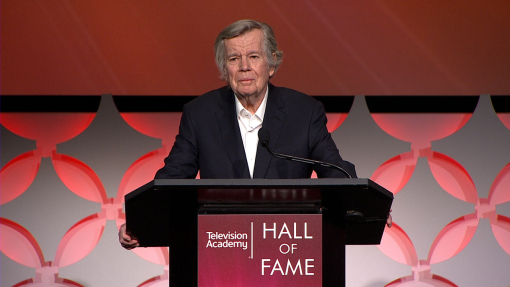

But Schieffer got the job, and now, at 76, he is the dean of the Washington correspondents, the only network reporter to have covered all four major beats — Congress, the Pentagon, the White House, and the State Department — as well as anchoring both the CBS Evening News and a short-lived morning show. He has been host of Face the Nation for the past two decades. He has won seven news Emmys and two Sigma Delta Chi Awards, and is a member of the Broadcasting and Cable Hall of Fame.

“He is a shoe-leather reporter,” says CBS Evening News anchorman Scott Pelley. “No one has more experience. No one knows more people.”

And quite simply, Pelley says, “Bob Schieffer saved CBS News.”

In 2005, Dan Rather stepped down after anchoring the news for 24 years, after the network acknowledged they could not authenticate documents used in reporting that President George W. Bush had received special treatment during his service in the Texas Air National Guard during the Vietnam War.

Schieffer was named interim anchor.

“Our reputation had been damaged, our future was in doubt, and he was able to right the ship immediately,” Pelley says. “He was the only person who could have done it. With his reputation for integrity and bipartisanship, he led us from that dark, dark night. He rebuilt the audience and rebuilt the reputation and set the news division on course. He saved the organization that he loves.

Seventeen months later, when Katie Couric took over, Schieffer said he was the welcoming committee. If he had been 50 years old, he told the Television Academy Foundation’s Archive of American Television, he would have wanted to keep the job himself, but at 70, “I wouldn’t have hired myself to do it.”

Back in CBS’s Washington headquarters, he moved into legendary news broadcaster Eric Sevareid’s old corner office.

“I’m the only one who knows it is his office,” he says with a laugh. “Everyone who might remember is dead or has been fired.” He’s not sure Sevareid would approve of what he’s done with it, covering the walls with about 100 photographs, some with world leaders, some with his colleagues, and some with the country music band Honky Tonk Confidential, with whom he makes sporadic appearances. He’s still hoping a major country singer will record one of the songs he’s written.

“Lately,” says David Rhodes, president of CBS News, “Face the Nation, which he has been doing for 20 years, is the number-one Sunday show, and obviously we are really excited about that.”

Rhodes credits Schieffer’s affable personality, and his many years in Washington, which add context to his questions. “While he was covering this last presidential inauguration, he commented that the first inaugural he attended was Johnson’s and the first he covered was Richard Nixon’s. So he always has that perspective. He’s seen it all. And the other thing he’s got going is something from his Texas heritage — he calls them like he sees them. He actually listens to the answers and he is quick to point out when what he hears doesn’t add up.”

Rhodes says Schieffer’s deft handling of the third presidential debate last October was characteristic.

The official transcript shows that when it was time for Governor Mitt Romney and President Barack Obama to make their closing remarks, Schieffer was having trouble getting a word in.

ROMNEY: Look, I love to — I love teachers, and I’m happy to have states and communities that want to hire teachers do that. By the way, I don’t like to have the federal government start pushing its weight deeper and deeper into our schools. Let the states and localities do that. I was a governor. The federal government didn’t hire our teachers.

SCHIELLER: Governor?

ROMNEY: But I love teachers. But I want to get our private sector growing and I know how to do it.

SCHIEFFER: I think we all love teachers.

“The whole crowd laughed. They had been warned to stay silent but they couldn’t resist, and that cut the tension,” Rhodes says. “I breathed a sigh of relief; this was going to be all right. Bob can get away with it.”

Schieffer still works six days a week — his wife Pat wouldn’t want him hanging around the house, he says with a laugh — and he’s looking to make the Schieffer School of Journalism at his alma mater, Texas Christian University, “the best journalism school in the country.” He has raised $5 million to create a state-of-the-art television studio, hosts an annual news symposium (inviting “the best and the brightest”) and tries to get down to the campus twice a semester to talk to students.

“If I were looking for a perfect model of a reporter,” says Jeff Fager, chairman of CBS News and the executive producer of 60 Minutes, “it would be Bob Schieffer. He’s a real reporter. First and foremost, he is naturally curious. He reads. He’s up-to-date. That’s so hard to come by. He knows how to ask the question, how to listen and how to follow up. He asks a question and the viewer thinks, ‘I’m glad he asked that.’ It seems basic, but it’s not. I can’t think of anyone better.”

Fager adds:

“We are so fortunate to have him at CBS News, and we have always felt that way. He has been the most respected reporter in the business for a long, long time. Nobody ever says that he got it wrong or that he treated someone unfairly. There’s so much special about Bob Schieffer. Thank God he works for us, because I wouldn’t want to be competing with him.”

This tribute originally appeared in the Television Academy Hall of Fame program celebrating Bob Schieffer's induction in 2013.